WILD THING: IMAGINED VIRTUAL REALITY SYSTEMS IN MARVEL COMICS' NIKKI DOYLE

by Julie Palsmeier

Although neglected by critical theorists, comic books are a rich site for exploring social issues, from AIDS to the Internet.1 In Nikki Doyle: Wild Thing (1993), Simon Jowett imagines both a Virtual Reality (VR) system and the societal response to it in a futuristic New York City.  In VR, teenagers project their bodies into a parallel interactive space in order to fight the forces of evil. While the Teen Age and its fascination with computer technology is not a new topic for theoretical debate, Nikki Doyle deepens our understanding of the interrelations between gender and psychoanalytic theories on technology, as they have recently been articulated by such theorists such as Avital Ronell, Sandy Stone and Laurence Rickels.2

In VR, teenagers project their bodies into a parallel interactive space in order to fight the forces of evil. While the Teen Age and its fascination with computer technology is not a new topic for theoretical debate, Nikki Doyle deepens our understanding of the interrelations between gender and psychoanalytic theories on technology, as they have recently been articulated by such theorists such as Avital Ronell, Sandy Stone and Laurence Rickels.2

Nikki's adventure begins in the New York of 2020 AD. The first images of the text are contextually vague: are super-heroes being killed by adolescents, or is this merely a VR game? It becomes clear within a few pages that this initial (or primal) scene is indeed a VR game in which adolescents fight and conquer super-heroes such as Spiderman and the Hulk. The adolescents' penetration into or inter-activation within this projected world allows them to inhabit two different spaces simultaneously. The living body doubles, and the body that remains in reality (CR as opposed to VR) appears to be in a coma. The assembled group of players becomes a line of corpses.

To enter into VR, players wear a headset with goggles and a dataglove, and are attached into a system that wires all of the headsets together. The players lie back and maneuver a joystick. Once they have entered VR, the group shares the holistic experience--or the hallucinogenic trip--as a group, realizing the fantasy, once articulated by computer guru Timothy Leary, of a group drug.3 Each fix is a repetition or recycling of mass suicide, a communal decision to leave this earth, and an addiction for the adolescent.4 The group has no leaders, and the players are unnamed, implying that they are homogeneous parts of the whole.

Everything would be purely fun if this group experience were an unending ride of fighting games and aggression, in which death never really occurred, except for the death of the adolescents' other (in this case the superhero). However, this battle with the other is actually a battle with/in the self, presented endopsycically in VR. In other words, the inner mechanisms of the psyche are exteriorized in a projection, made visible to observers.

The adolescent not only fights and kills the super-hero, but struggles with the super-ego, desiring pure ego and a world of replication rather than reproduction. Reproduction breaks apart this group, which perceives coupling as an unfaithful departure to the mortal adult world.  However, the desire for immortality in VR is threatened by a super-egoical force that can never be killed: a phallic threat appears to the maternal group in the form of a fiery, flaming father figure, descending upon the unnamed adolescents.5 Playing a double role, this phantom of the father is both Prometheus and the devil, at once the prohibition of homosexual desire and a death threat.6 His three-pronged pitchfork zaps the players, causing them to double eternally in VR, while their corpse remains in CR. However, total annihilation of the body does not occur; rather, the adolescent doubles once again. While the body in CR is a barbecued stiff, a charred skeleton, the body in VR wanders around as a ghost in an eternal aggressive mode.

However, the desire for immortality in VR is threatened by a super-egoical force that can never be killed: a phallic threat appears to the maternal group in the form of a fiery, flaming father figure, descending upon the unnamed adolescents.5 Playing a double role, this phantom of the father is both Prometheus and the devil, at once the prohibition of homosexual desire and a death threat.6 His three-pronged pitchfork zaps the players, causing them to double eternally in VR, while their corpse remains in CR. However, total annihilation of the body does not occur; rather, the adolescent doubles once again. While the body in CR is a barbecued stiff, a charred skeleton, the body in VR wanders around as a ghost in an eternal aggressive mode.

The VR ghosts form their own group, and encourage other living and dead adolescents to join them. The group shares the dream of eternal group bonding; they are friends engaging in unending warfare. The phantom group has triumphed over the super-ego, thus attaining immortality. They turn on (and off) the living adolescents, killing them in CR as they are initiated into the VR gang. Ironically, the phantom group abandons their "maternal" status, thus doubling the role of the father by acting as a super-egoical threat to the living group. They are a projection of the policing system in CR that attempts to bust up VR addict rings.

The players who are still alive in VR lack an ego-ideal. The only player capable of leading the pack out of danger has been abducted by the state. Nikki, an imprisoned VR addict who against her will becomes a daughter of the state, aids the police in arresting illegal VR sellers and users. Like a ghost returning from the dead, she once again enters VR dens, but now as a tool for the father rather than a member of the group. Not surprisingly, in her first appearance in the comic she bears a striking resemblance to the ghosts in VR.

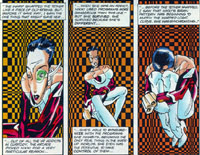

This alignment with the phantom group is quickly undermined as she enters VR. Once plugged in, she takes on the typical appearance of a comic heroine--a muscular body with large breasts, drawn in sexual poses.  Her transformation bears a striking resemblance to Sandy Stone's vision of how computer technology is gendered: The adolescent male within humans of both sexes is responsible for the seductiveness of cybernetic mode, and when the "console cowboy" enters cyberspace, he puts on cyberspace. To become the cyborg, to put on the seductive and dangerous cybernetic space like a garment, is to put on the female. However, Nikki's cross-dressing occurs in the other direction. She puts on the male as soon as she has left the world of VR. Her sexuality in relation to VR is ambiguous from its origins.

Her transformation bears a striking resemblance to Sandy Stone's vision of how computer technology is gendered: The adolescent male within humans of both sexes is responsible for the seductiveness of cybernetic mode, and when the "console cowboy" enters cyberspace, he puts on cyberspace. To become the cyborg, to put on the seductive and dangerous cybernetic space like a garment, is to put on the female. However, Nikki's cross-dressing occurs in the other direction. She puts on the male as soon as she has left the world of VR. Her sexuality in relation to VR is ambiguous from its origins.

Nikki's VR history begins at Christmas in the 1990s, with a gift of a video game from her mother. A shot-by-shot history of VR addiction combines Nikki's history with that of other addicts, blurring the lines between herself and male adolescents. Like false match-on-action shots in film, the characters have been switched, and Nikki is replaced by a boy. Nikki possesses a special quality among her addict friends, because she is the most successful of the illegal VR players: Out of all the VR addicts in custody, the arcade picked Nikki for a very particular reason. When she was an addict, Nikki used programs more dangerous than this one--but she survived. She survived because she's different...she's able to synchronize with the programs she inhabits, becoming the only real thing in the made-up worlds. She even has the potential to take control of them (Book 1). Nikki's ability to merge with the warped logic curve ensures her survival. When she synchronizes, she assumes a fetal position, as though she were back in the womb, a space constructed as privileged and accessible only to a woman. The other characters envy her ability and control in this VR system. Nikki embodies the adolescent desire to control the all-powerful mother, yet, as Avital Ronell argues, the womb of VR takes on patriarchal forms, becoming altered and dangerous.7 The womb in this adolescent fantasy is also a tomb.

Each rebirth from this close encounter with the real sends Nikki back into VR where she encounters super-heroes that must be killed. Nikki's matrilineal inheritance of technology permits her to save men from death by the father. Yet she performs a double role when hired by the state. She saves the gang from the Father, but also saves them in the name of the Father, bringing them back onto the side of law, plugging them in to the patriarch. The adolescent cannot win the game...all of his projections turn against him.

Nikki Doyle: Wild Thing is obsessed with the idea of doubling, or replication. Every death in the comic leads to replication. Whereas the adolescent becomes an "unmourned" in VR, the super-hero splits into a double super-hero, but only when at the mercy of Nikki's blaster. When she blasts the super-hero, he becomes two characters, joined at the hip. This doubling alludes to a homosexual bonding, in which all three characters appear to be engaging in anal sex. Once again, Nikki's gender role is male, albeit in a passive position. The super-hero does not fulfill a death wish, yet Nikki's gun visually brings the super-hero into line with other adolescent desires: for replication, and here, for sex with the father.

Nikki's double-gendered alliance to the father also allows for heterosexual reproduction, and her merger with the state breaks the bond that she held with the other guys in VR. She inhabits the space of conflict between the group and the couple, between the body and the future.8 But, even in her most sexual posturing as a female, Nikki is drawn as though she has a double phallus attached to her thighs. In the final scenes of Book 2, she finds a man in VR who is also able to synchronize with the program, and hopes that by substituting him for herself she can leave the world of the Father: Nikki: "If you got here the same way as me, no wonder you're in shock. Maybe you've got some of what makes Liddel and Trout so interested in me...maybe I could arrange a trade--you for me... let's go see" (Book 2). Yet this character appears very similar to the character Prometheus, alluding to an eventual alliance with the father. Later it becomes clear that he will not be a successful replacement for Nikki, and this is due to the fact that he is not a she, and not capable of performing the role of ego-ideal for the maternal group. As Nikki is contemplating the trade, she grabs hold of her own protruding phallus and his, and during this sexual moment sends them both back to CR with the words "Wild Thing." This "same" sex experience saves group members both from the couple and the father, yet the threat is always there, lurking in VR.

These last images prior to take-off also contain one last image of Prometheus flying through the air. Nikki and her same-sex pal have accomplished a homosexual experience despite the threat of this figure, and they've escaped the projected world of phantom fathers. Upon arrival to CR, they are both sweating and aching (the dataglove overloaded). At the same moment, an Uzi shoots into the VR den and explodes in what appears to be an apocalyptic moment. However, as in the projected world of VR, these group suicides are always repeated and replicated, as issues 3, 4, 5, and 6 demonstrate.

The comic book, as a form of fiction, replicates the same heroes, again and again, eternally replaying the same narrative. Each new episode is a return from the dead. The monthly appearance of the comic book on the shelf recalls the menstrual cycle of the young woman who regulates the group.9 Monthly purchase of the comic becomes part of the teenager's initiation into adolescence and the feminine cycle.10

Teens write to the comic and voice their desire to buy the next issue. Others identify with Nikki. Joseph from Florida writes, "I quickly opened the cover to be totally surprised to see my favorite heroes dead...I felt addicted to it, as Nikki is to VR...." Identification with the adolescent group and fear of the father (in CR & VR) allows for total conversion among adolescents. Matt from New York complains, "My father says that reading comic books is for dummys [sic]. I do not believe he is right." Reading comics is a form of resistance to the father, as are VR and drugs. This addiction is a refusal to disconnect with the group, and thus a desire to remain connected to the other members of the gang (and the other. members' members).

These fans hark back to the corpses lined up in the opening pages of Nikki, representing a space in which the group interacts together but at long distance. The attraction to VR is that it allows the disconnected or doubled body to meet and interact with other members. While many fictional master narratives call for conforming to the One--the Father--this comic offers a site of resistance to the One. Unfortunately in America and in the UK, this resistance is not taken seriously by the Father or the alma mater.

Fans write about their attraction to the comic and the comic's authors. Benjamin: "I haven't seen artwork this mouthwatering...Steve Whitaker's colors are mind-blowing; they make the art just jump out and grab me...." Alan: "I hope #2 is just as exciting and suspenseful as the first...." Kris: "This comic sure gets the blood pumping." The visual text becomes a sensual experience for the adolescent, who becomes turned on when plugging into Nikki's universe. Plugging into the serial text becomes an outlet for adolescent libido, with an endless amount of feedback. Therefore, it is no coincidence that some of the first computer texts are comics, and it will be no surprise when interactive movies mirror combat with super-heroes.

Finally, as a footnote, this 1993 comic serial directly responds to La Femme Nikita, which came out in France in 1991. This film opens with a drug-addicted gang breaking into one of their father's stores for drugs. Nikita can not be distinguished from the other members of the gang, who all appear to be male. The state kills the gang and arrests Nikita. Feigning her death, the state gives birth to a new and improved Nikita, who now works on the right side of the law, serving the patriarch and blowing away the bad guys.  Before capture, her gender performance is both masculine and feminine, yet the state eventually manages to put her into a pair of 5-inch heels and a mini-dress (with a gun between her breasts). Nikita's ultimate refusal to be plugged in to the patriarchy leads to her disappearance from the screen. As she can no longer have access to the gang outside of the law, as her own femininity is falsely inscribed on her body as a patriarchal trap, she attempts to function as a doubled contradiction, and vanishes forever.

Before capture, her gender performance is both masculine and feminine, yet the state eventually manages to put her into a pair of 5-inch heels and a mini-dress (with a gun between her breasts). Nikita's ultimate refusal to be plugged in to the patriarchy leads to her disappearance from the screen. As she can no longer have access to the gang outside of the law, as her own femininity is falsely inscribed on her body as a patriarchal trap, she attempts to function as a doubled contradiction, and vanishes forever.

By contrast, at the end of Book 2, Nikki Doyle is not effaced from either VR or CR. Rather, she continues to play a multi-gendered role in the comic. Although super-egoical forces are at hand in both spaces, there does seem to be resistance to these forces from within the adolescent group. The tensions between the Teen Age and the Father are never resolved: they are replicated again and again each month in installments of Nikki Doyle. Nikki's multi-gendered role not only brings to light the gender blurring that occurs within the adolescent group, but also alludes to the process of cross-dressing that occurs across VR technologies.11

Nikki's adventures with the group are thus a mise-en-abyme of the comic form, which replicates the same narrative every month. Readers of comic book serials also "put on the female," and correspond both with the form of the comic, the technology itself, and with other participants as well, responding to the stigma that parents and society attach to what is often considered a low-art form. Like Nikki, the comic book confronts the tension between the adolescent group (readers) and the Father (society and even high literature), in order to expose and challenge those systems.

Notes

1. See Marvel Comics 2000 series or Shadowhawk.

2. Stone, Sandy. "Will the real body please stand up?" Cyberspace: First Steps. Michael Benedikt, ed. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1993, 81-118 and Laurence Rickels, The Case of California Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1991).

3. Woolley Benjamin, Virtual Worlds. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992.

4. Rickels, The Case of California.

5. Rickels, Case, 168.

6. Rickels, Laurence A., Aberrations of Mourning Detroit: Wayne State UP, 1991, 221.

7. Rickels, Aberrations of Mourning; Ronell, Avital, "The Walking Switchboard," Substance 61 (1990), 74-84.

8. Rickels, The Case of California.

9. Rickels, The Case of California, 172.

10. Rickels, The Case of California, 176.

11. Stone, "Will the Real Body Please Stand Up?"