KLAUS THEWELEIT'S _BOOK OF KINGS_: EXCERPTS IN TRANSLATION

by Klaus Mladek

"[...] Why do I need a 'principle hope', if I have

certainty through rock'n'roll [...]

marxism won, but in the disco:

the mute on earth

the dumb, fool and therefore underprivileged

they articulate themselves with rock'n roll

millions of human beings who before on the round earth

didn't have anything to say

you don't even need an instrument

simply think of a sound"

--Wolfgang Neuss; Everybody Has His Own Blues Anyway.

(one of Theweleit's favorite poems, v. 2y, page 222)

In the Beginning was Cannibalism

In his third huge volume of The Book of Kings, volume 2y, Klaus Theweleit finally leaves the dark realm of fascism and national socialism. The detective Theweleit convicts the kings of poetry, philosophy and theater--Benn, Pound, Celine, Hamsun, Heidegger--of crimes and murders.  Artist-kings are revealed as cannibals and their kingdoms are built (gepflastert) with corpses (particularly female) and blood -- as are the kingdoms of usurpers, statesmen and dictators. Orpheus and Eurydice is the subtitle of the first volume The Book of Kings. The modern art kings in Theweleit's new reading, the kings of pop, literature and art, suck their victim's blood, incorporate and consume them, force their "medial women," helpers and beloved into suicide or death, leave or ruin them, in order to be able to bear witness then to their unbearable suffering from the loss of the lover. Theweleit calls the relation between Orpheus and Eurydice a "Hades-connection." The natural product of these "medial bridges" into the beyond has always been the "beautiful" work of art of the "genius king." The uncanny ambivalence of art production as death-giving while at the same time, creation. The crypt of the dead medial woman survives as a stimulation of art production and, from that point on, haunts his work. But Theweleit expands his line of questioning: What strategies does the modern art king employ for his art production? How do we vault our idols and stars into their royal status? What happens when their narcissistic ambitions stretch out across the fields of power ("power pole") in their dealings with political leaders or when their kingdom is challenged? How does the interchange between power, love and art production function? And finally, is there such a thing as a typical psychical constellation of the modern artist?

Artist-kings are revealed as cannibals and their kingdoms are built (gepflastert) with corpses (particularly female) and blood -- as are the kingdoms of usurpers, statesmen and dictators. Orpheus and Eurydice is the subtitle of the first volume The Book of Kings. The modern art kings in Theweleit's new reading, the kings of pop, literature and art, suck their victim's blood, incorporate and consume them, force their "medial women," helpers and beloved into suicide or death, leave or ruin them, in order to be able to bear witness then to their unbearable suffering from the loss of the lover. Theweleit calls the relation between Orpheus and Eurydice a "Hades-connection." The natural product of these "medial bridges" into the beyond has always been the "beautiful" work of art of the "genius king." The uncanny ambivalence of art production as death-giving while at the same time, creation. The crypt of the dead medial woman survives as a stimulation of art production and, from that point on, haunts his work. But Theweleit expands his line of questioning: What strategies does the modern art king employ for his art production? How do we vault our idols and stars into their royal status? What happens when their narcissistic ambitions stretch out across the fields of power ("power pole") in their dealings with political leaders or when their kingdom is challenged? How does the interchange between power, love and art production function? And finally, is there such a thing as a typical psychical constellation of the modern artist?

National socialism and fascism are the background of the first two volumes of the Book of Kings. Benn, Celine, Pound, Hamsun, Heidegger are Theweleit's kings; he describes how they hate, betray, denounce or collaborate with Mussolini, Hitler, Goebbels; how they finally lose their innovative energy, but still survive: The artist is no longer a seminal genius but a strategist, rather a variable form of energies, which can be translated artistically, vampiristically, cryptically. The artist-as-survivor relates at the same time to Theweleit's central figure of the Nichtzuendegeborenem (never-fully-born) for whom art production is a continuous resurrection and birth.

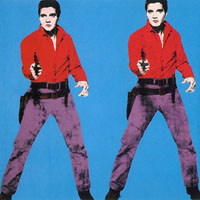

In the third volume, 2y, style, atmosphere and thoughts suddenly change. Theweleit leaves the shadowy realm of fascist guilt behind and goes to America, to the paradigmatic pop empires of Elvis (gang structure) and Warhol (band structure), to Bob Dylan and John Lennon--the idols of Theweleit's youth, leading figures of the 1968 generation who introduced new paradigms into the discussion of art.  In this volume his text circles around pop- and sub-states, series, crowned anarchies, excesses, nomadic dispersions of signs, singles, cans, revolvers, soups, shoes, cameras, videos, comics and films. Theweleit, the scratcher, sits on the mixing board, the words enter the dance floor, dislodged from their "proper" place. His book competes -- as McLuhan predicted--with other media. Elements of film, computers, video clips and comics form a text-image-sound collage which supercedes and dusts off old-fashioned cultural critique. That's how Theweleit sees himself, the enfant terrible of academic scholarship. The first two volumes, like his Male Fantasies, were already an unconventional and loose montage of pictures, songs, sounds and texts, but his last volume on American pop culture is literary MTV and touches on the problem of the readability of texts in general. Finally the words are set free.

In this volume his text circles around pop- and sub-states, series, crowned anarchies, excesses, nomadic dispersions of signs, singles, cans, revolvers, soups, shoes, cameras, videos, comics and films. Theweleit, the scratcher, sits on the mixing board, the words enter the dance floor, dislodged from their "proper" place. His book competes -- as McLuhan predicted--with other media. Elements of film, computers, video clips and comics form a text-image-sound collage which supercedes and dusts off old-fashioned cultural critique. That's how Theweleit sees himself, the enfant terrible of academic scholarship. The first two volumes, like his Male Fantasies, were already an unconventional and loose montage of pictures, songs, sounds and texts, but his last volume on American pop culture is literary MTV and touches on the problem of the readability of texts in general. Finally the words are set free.

Theweleit plays excessively with words and his games rest upon a very optimistic notion: The network of signs, series and media sets free the anarchistic power of words. The text itself as a medium approaches a multimedium that affects and subverts all fields of power and creates a space of undercurrent movements which exist beyond, within, or even above political states. Thoughts and their power become eroded from the inside because they migrate into the technical recording industries where they will be pulverized and disintegrated.

Rock'n'roll and modern media are revolutionary for the generation of the "pop born," the old myths remain, but they are reinscribed, transformed, simultaneously banalized and deepened. Walter Benjamin's "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction" echoes throughout Theweleit's project. The media, through which all experience is mediated, forces thought to change; the detour over the material drives the spectator to delay, decenter and destabalize the process of reappropriation. The pop kings create a new perspective, as Myths and Artists. As human beings they are in danger of perishing--the result of a merger with their uncanny doppelgnger, the star (whether super or mega or regular).

Theweleit becomes himself a "rock poet" (as he called Benn) of the royal rhizome; a "rocking writing," a stream of unconsciousness and a dissemination of various data is set in motion which not only represents but tries to embody the network of king's stories. The Book of Kings becomes an ecstatic dance, a data-overloading and mixing, scratching, surfing on the surface of popculture backed by solid humanistic knowledge. Image, rhythm and sound are supposed to drag the reader onto Theweleit's anarchistic dance floor, which is at the same time the mark of modernity. And Theweleit rolls the letters, Elvis lives still powerfully ("el vis") in veils and returns as an unfolded anagram of his name in the media-industry-artist complex.

The modern artist is an obsessed serialist, always desperately filling the dead center of his decentered subjectivity.  Warhol is the embodiment of the modern recording angel, an undead ghost, a party vampire, his body, zippered with scars is the striking sign of the distorted body/mind relation. What remains? A man without qualities, anonymous, sexless, a despotic perception machine, an empty spaceless disc player with a public exhibited body: The calculated public erasure of the artist as a person, "And(rog)y(n) Warhol," anticipating Michael Jackson and pop as anti-death and interruption of life at the same time. A kind of supercapitalism characterizes, according to Theweleit, the modern artist, who is already there, where the capitalistic circulation of goods has not yet arrived, and where series are radically democratic. Everyone, whether a Roosevelt or a Liz Taylor, eats the same hot dog, drinks the same Coke, and slurps the same Campbell's soup. The USA itself is a democratic series "of 50 stars and 500 branches" (2y, p.447), as stars, roses and cans.

Warhol is the embodiment of the modern recording angel, an undead ghost, a party vampire, his body, zippered with scars is the striking sign of the distorted body/mind relation. What remains? A man without qualities, anonymous, sexless, a despotic perception machine, an empty spaceless disc player with a public exhibited body: The calculated public erasure of the artist as a person, "And(rog)y(n) Warhol," anticipating Michael Jackson and pop as anti-death and interruption of life at the same time. A kind of supercapitalism characterizes, according to Theweleit, the modern artist, who is already there, where the capitalistic circulation of goods has not yet arrived, and where series are radically democratic. Everyone, whether a Roosevelt or a Liz Taylor, eats the same hot dog, drinks the same Coke, and slurps the same Campbell's soup. The USA itself is a democratic series "of 50 stars and 500 branches" (2y, p.447), as stars, roses and cans.

Warhol's "Campbell's Tomato Soup" is not only a self-portrait, but even stands in for the nude; the female body disappears: "the can occupies exactly the place, where art historically/theoretically the WOMAN in painting [...] was located" (2y, p.579). And in the can is neither a tomato nor a woman; the modern serial model is empty like Warhol's Campbell's cans, like the supermodel Naomi ("Norma", p.579) Campbell, "I'm a model, you know what I mean?"

Some problematic points in Theweleit's theoretical approach need to be mentioned; the almost incompatible relation between "power pole" and "art pole" is a fragile construction. The art pole is not an innocent counter-discourse, but functions also according to the rules of a normalizing power.  Theweleit's presupposed autonomy of the art pole, delineating itself from political practices, is imbedded in a certain rhetoric of power: the statement of the existence of power-free spheres in the discourses of art is exactly the condition of its authority. Even assuming a functioning separation, one could say with Adorno: "There is no right life in the wrong one," l'art pour l'art still contains a power-related attitude toward society. Even in the most anarchistic art production, the inescapability of power is apparent, since power is precisely that against which anarchism protests. One might consider not just art and power, but art itself as a field of power, and power reflected in art production, as well as the notion of power as art -- all of this could be investigated. Theweleit's strict separation is difficult to defend and obscures these dynamic and complex interactions.

Theweleit's presupposed autonomy of the art pole, delineating itself from political practices, is imbedded in a certain rhetoric of power: the statement of the existence of power-free spheres in the discourses of art is exactly the condition of its authority. Even assuming a functioning separation, one could say with Adorno: "There is no right life in the wrong one," l'art pour l'art still contains a power-related attitude toward society. Even in the most anarchistic art production, the inescapability of power is apparent, since power is precisely that against which anarchism protests. One might consider not just art and power, but art itself as a field of power, and power reflected in art production, as well as the notion of power as art -- all of this could be investigated. Theweleit's strict separation is difficult to defend and obscures these dynamic and complex interactions.

The "power pole" in Theweleit's reading functions as the bad, corrupting agent, which drags the art pole into its unproductive wake. Whenever Theweleit sounds moralistic, he approaches Frankfort School criticism, perhaps much closer than he would like. Also the "power pole" is as monolithic as the "art pole," the variety of strategies and different fields of power are left unaccounted for. In this version, there is only one power pole.

The perception of what is considered to be art or an artist is filtered through a variety of mechanisms of power which inescapably title, name, determine and circumscribe the king's space. The medial women, helpers and mediators as independent personalities are uncannily excluded from the start, and all attention is focused only on the king's head, its mechanism, psyche and ambivalence. The Book of Kings is fascinated by the biographies of kings, with their magic power and their opaque art states, and so deals with the perhaps unavoidable dilemma of silencing the victims once again. The problem is more concerned with the relation of Theweleit's two favorite words: myth and media. If the modern media and the innovations of rock 'n' roll were really able to "restructure the brain," how could certain patterns of mythical constellations and archaic actings (e.g. Orpheus, Eurydice, Pluto, the Chorus) survive modernity without essentially changing their face? Can media change our perception so much that these "eternal" myths lose their attraction, or can they even fortify mythical power? Why does the media then, as Theweleit insistently shows, reproduce and establish stars, myths, images, kings' positions, and power relations instead of enacting their utopian strength on the "pole of weightlessness"?

Theweleit describes the modern artist within a certain context of (psycho)logical predispositions, crypts, milieus, family structures, but does the artist's energy really flow according to these mythical and psychic constellations? Many other modern artist kings don't seem to follow the patterns which Theweleit finds for Andy and Elvis, as the representatives of modern pop culture.

Theweleit describes the modern artist within a certain context of (psycho)logical predispositions, crypts, milieus, family structures, but does the artist's energy really flow according to these mythical and psychic constellations? Many other modern artist kings don't seem to follow the patterns which Theweleit finds for Andy and Elvis, as the representatives of modern pop culture.

Theweleit's very entertaining and innovative study on American culture ends up resembling other recent European essays on the USA, such as Eco's Travels in Hyperreality and Baudrillard's America. The European fascination with "America" as a country of postmodern ecstasies, gigantic series, and hyperrealities certainly hits on many projections and fantasies. But can these studies really describe some central features of the very inconsistent, heterogeneous, complex and extremely problematic variety of American culture?

(I would like to thank Kristin O'Rourke for help with this review.)

Translation Excerpts from the Book of Kings

Let's now finally enter Theweleit's dance floor, which often reaches the limits of readability. His "rocking writing" (2y, p. 293) -- as competing with other media -- distorts and disintegrates the linear textual structure. Pop culture, modern literature and the current media set the signifiers free -- a freedom which Theweleit's text performs. But the old interchanges of art and power remain, the modern pop-artist is still a power-strategist, a Narzi (2y, p. 343). This selection of text-passages (most from volume 2y) gives a dazzling impression of how the interactions between Theweleit's writing, media, modern literature, myth, power and seriality function within this project, the Book of Kings.

Ruth is the drives

[...]The news hasn't gotten around (in spite of Joyce and Arno Schmidt) that although thoughts aren't free, words certainly are. They are (via recordings, film and television) relieved from -- and of -- their position as Number One controlling media power.

People, these curious human beings, accustomed to the commando-function of words persistently refuse to recognize them. They do not play with words.

They let words continue to play the police. And the words, who would otherwise starve, play along listlessly. (v.1, p. 1)

[...]Driver's license, theory. Diedrichsen: ' I didn't just learn English from songs and today I still speak English which consists only of quotations: [...)]when I say/think 'Fire Brigade,' I hear a song by The Move, and I have also learned thought from Pop music. That the ego has limits. That human beings are conditioned. That one can put oneself in another's place and that one is really actually inside the other. That one should drive down a mountainside on a hot summer day without steering. That one is always right to hate. That it is beautiful to be deathly ill from drugs. That whatever you want, is always right -- which only the pop-generation knows again, since the duty-bound of 1870 to 1940 left no possibility of desiring to prove otherwise: that, that which one may not want anyway, must be done (and unconditionally at that).

[...]Driver's license, theory. Diedrichsen: ' I didn't just learn English from songs and today I still speak English which consists only of quotations: [...)]when I say/think 'Fire Brigade,' I hear a song by The Move, and I have also learned thought from Pop music. That the ego has limits. That human beings are conditioned. That one can put oneself in another's place and that one is really actually inside the other. That one should drive down a mountainside on a hot summer day without steering. That one is always right to hate. That it is beautiful to be deathly ill from drugs. That whatever you want, is always right -- which only the pop-generation knows again, since the duty-bound of 1870 to 1940 left no possibility of desiring to prove otherwise: that, that which one may not want anyway, must be done (and unconditionally at that).

It is also to be expected that (and millions of my contemporaries who have grown up in the same way discovered) intelligence in music was the means for them to develop their understanding. Earlier people developed themselves, we say, from observing the heavens and earth and fire and water and, logically enough, found their gods there. We found ours in Pop music.

Whoever takes seriously the 'fundamental conceptual character of all pop music,' of which Diedrichsen speaks, can no longer be an idiot or materially unsophisticated.

A theoretical discourse (Learning) has set itself in motion, in which the collision of sensory organs and tools/media gains consciousness of itself and operates accordingly. The practical-abstract intelligence of the tool/media passes into the user and restructures his brain. (v . 2y, p. 223 ff)

The legends of art and power deal primarily with what happens when people begin to confuse themselves with their legends, in the evening when they come home from their games, when they and their country are not fourteen anymore, when they are adults and meet with the Greats or the Greatest and want to mix the legend of power into their own selves.(v. 2y, p. 2)

Power to the People

[...]Perhaps someone who doesn't' belong to "art-states" or know anything about them can doubt their existence: their governing inhabitants see themselves as statesmen and behave as such... Elvis, [Gottfried] Benn, Pound, Michael Jackson, Hamsun, Celine, Maxime Gorki, Malraux, or (with no direct authority) Thomas Mann; those who command or otherwise direct the art- or pop-state live, sometimes temporarily, sometimes continuously, in the self-evident certainty of having diplomatic relations with political leaders of parallel national or police states.

The certainty of the art-state's autonomy (which in the meantime has been realized in the autonomy of Media-Worlds) led Elvis and Benn to the President/Fhrer of their countries. Nothing, not the primacy of the economic, the political or the soldierly, stands in their way -- late offspring of the Orpheus/Pluto pairs of the renaissance courts.

In the twentieth century it is often deserted Kings who go to look for Pluto, if Pluto doesn't come of his own accord... Kings, whose lands are worked by others, by shameless usurpers... Businessmen they drink my wine, ploughmen dig my earth... Chosen ones continuously acknowledged.. without valid artist-diplomat passport for the palaces... between worlds... unplugged... Eli, Eli lama... and it drives them to the Whitehouses, the Academies, the Fhrer's Chancelleries... and they are the worst scumbags in their aspiration to be blessed by the Masterpig, in order that the wire on which their world is stretched does not break... they don't exactly lick boots, but... without losing a beat... fall into the same rhythm, the rhythm of power, hard caesura, upon which speech is enacted (not even a song), whosoever does not acknowledge me, whosoever supplies no troops to defend my state, him shall I help to crush.

In the twentieth century it is often deserted Kings who go to look for Pluto, if Pluto doesn't come of his own accord... Kings, whose lands are worked by others, by shameless usurpers... Businessmen they drink my wine, ploughmen dig my earth... Chosen ones continuously acknowledged.. without valid artist-diplomat passport for the palaces... between worlds... unplugged... Eli, Eli lama... and it drives them to the Whitehouses, the Academies, the Fhrer's Chancelleries... and they are the worst scumbags in their aspiration to be blessed by the Masterpig, in order that the wire on which their world is stretched does not break... they don't exactly lick boots, but... without losing a beat... fall into the same rhythm, the rhythm of power, hard caesura, upon which speech is enacted (not even a song), whosoever does not acknowledge me, whosoever supplies no troops to defend my state, him shall I help to crush.

Narcotic... Narcissus... Narcissism... Nazi?

No. It has nothing to do with insults like "wounded self-esteem" or in emotional positions such as "abandoned son" (of the great God's Art). There are positions of power and there is the King of kings of art production. Whoever denies or underestimates his existence touches a powerful force field and should not be astonished when a hail of jolting blows comes from it, electrical and other, crueler ones...

... one can know that (if one is not completely stupid). See how they run... a couple of bones crack, at least there should be a certification of an undiminished existence as a king (BNDD Badge, a president's chair, a broadcaster's license)... One had tried to turn off the tap of their artistic production... tried to take their world away... there is no mercy here... the rage is "pure," sharp, genuine in the heat of the moment that the political superpower is touched... their own power grows out of rage, that power, which is so rapidly disappearing from their enemies.

The revenge smacks of "legality." I would not call it "just;" but in regions and countries where political and other social forces are not at all shy to represent and execute the claimed legitimacy of their self-defense openly with weapons of state or other homemade violence, the anger of the kings of art is not of a less plausible kind. Should he of all people, the creator of rapturous beauty, whose beauty is destroyed (in the name of other ecstasies or political contingencies) be the apostle who turns the other cheek? If he reflects, perhaps. If he has support; if he is not alone but connected by one, two friendly power-giving circles...but in the heat of isolated resentment? No, he will not. (v. 2y, p. 339 ff)

What is a series?

A series (as distinguished from industrial serial production) is to do something again and again, but with a little variation. "Series" is the art of the minimal deviation from the same. Nowadays "the individual" may possibly be located in this small deviation. (v. 2y, p. 452)

Stones, Cans and Roses

A flower got the stone rolling -- the foundation stone of the series.

a rose is a rose is a rose is a roseIn this line (this assembly line of letters... this telegram from the pole of weightlessness) a rose is "red again" for the first time in one hundred years of literature -- as Gertrude Stein loved to claim. Not that she "meant" that. This was her PR-line "for the folks down home in the college."

a rose is a rose is a rose is a roseis an endless loop... is a rolling stone... is an answering machine... is a moving car (Gertrude's Ford)... is a series of roses... is scents... is a series of noses... is there are serial productions (in Pittsburgh)... is there are explanations (in Harvard)... is there are incantations (in Paris)... is there are girls... is there are roses... but they don't exist in the same sentence.[...]

Generators hum. A clear ear, that allowed itself to be drawn into the hum of the reeling rose, drawn into the cycle -- 33 RPM: the invention of the LP in literature -- has mistaken the murmur of this secularized rosary for the following:

a rose is eros is arrows is sorrows... is a white rose is a red rose is a yellow rose is a black rose...

In cycles of opening and closing rose petals the wheel of birth/love/death/birth... life as a series... love as a series... you can turn the wheel endlessly.[...]

... a rose is a rose is a rose is a rose is the whole heaving ocean in the emptiness of a single line... is the discovery of the assemblyline in letter production... is the world in balance... is the hissing of all grounded channels... is the chance for the trance... is Everybody Must Get Stoned.

A rose is its own movement, as Henry James grasped in Gertude's rhythm the secret of New York: In New York appeared the universal move to move, move, move as an end in itself, an appetite at any price. -- a rose is a move is an empty necessity, is the Mother of Invention, is the desire to desire[...]

With Warhol the wheel is turned further. A rose is a rose is a rose the aristocratic series of the literary class of Upper Pittsburgh is translated or stamped into the steelworker's city's service a can is a can is a can is a can... is acrylic on can-vas... now it is our turn (acrylic roses, unlimited).

[...]Campbell's Tomato Soup... the most quoted image in American painting (a rose is, in another part of the city, a tomato).

When one mixes the production line of "a can is a can is a can" with the Sound of Pittsburgh's suburbs or with any American or Liverpuddlian dialect, from the noise of the labeled tin come quite clearly the words

I can is I can is I can[...] "I can make it in America." Said Elvis (said Warhol) in the direction of Mother, in the direction of his audience...(Said Gertrude Stein in the direction of her brother Leo) "Yes you can," said the people. And Elvis (Andy), astonished: "Oh, they really like me." (In Stein's case it resulted in contradiction from her brother Leo, the Renoir collector: "No, you can't." Picasso had to come... "oh, he really likes me.")

Elvis' school days before the discovery of "I can sing Madam"... "I can play the guitar"... a hell. Similar for Warhol, including before school. It was not easy to be a painting pale face among immigrant Working Class Heroes.

But it's alright, Ma. I can make it...Sums up the song which describes it best.

... it's alright Ma. I'm only bleeding (I'm not dying)... I'm only wounded... I'm only discovering, I'm just another one who screams... don't be frightened when a trembling voice reaches your ears... It's alright Ma... it is my... I'm only sighing...

And although the masters make the rules... for the wisemen and the fools... it's alright Ma... I can make it. He could -- Bob Dylan.

... the masters with the masterpieces...

As Picasso died, I read in the newspaper that he had made 4000 masterpieces over his lifetime. I thought "C'mon, I can do that in one day." In my manner, using my technique, four thousand a day. And they would all be masterpieces, because they would all be the same painting.

because

a rose is a rose is a rose is a can

... is a Cezanne... is a Matisse... is a Picabia... is a Picasso... is a silk rose... is a

new rose "now"

The guy doesn't make jokes... the artist/God never makes jokes... he always makes jokes... but most of all he lets his technique respond... Technique 4000 times per day... 33 revolutions per minute... 24 truths per second... I can is I can is I can...

... and when he analyses: of Picasso's 4000 masterpieces, 3000 are also "the same" painting: serial to European conditions (series production with a certificate of uniqueness)...[...]

... but if my thoughts could be seen they'd put my head in the guillotine, sings Dylan (says Warhol, says -- finally -- Elvis as well; says Gertrude Stein...) But that doesn't matter:

It's life and life only...

Dylan's song really ends in such a wheel of roses. Not tautological, but serial

a life is a life is a life (only)

alive is alive is alive... and as long as a rose is eros is arrows is sorrows is a can is I can -- I can make it: songs, 4000 masterpieces a day ... 1 thousand films in 1 lifetime... 3 thousand recorded songs... 1 billion words (all of them masterful).

So says, I think, the sentence of the serialists: "I am not, but I can do it." A sentence meant to fill the void (with around 4000 masterpieces per day).You can die in peace now, I'll be alright, Ma. (v. 2y, p. 430 ff)

Quantum Energy, Power Physics

Without pretending to be Einstein, one could take as a point of departure the social energy quanta which transform themselves into power quanta.  Every human society creates a certain amount of power which is the direct result of the gross national product. The more technical the society, the higher the amount of power which is created. Its production power includes the production of gods as well as presidents, space ships, types of people, and types of artists: it includes the creation of Great Artists and the absolute Ruler Artists. The places of power in highly technical and governmentally "democratic" societies are filled following a vacancy. No one simply "inherits" them. There are no dynasties into whose laps power falls. The canvas is empty. You must fill it... the place of artistic power is correspondingly empty of personnel. You can fill it... a sentence for those people with great quantities of free-floating production energy may take this form: you must enter into it -- that is, whenever other social production locations are in acute shortage or whenever this position is obviously occupied by an "incompetent," or usurpers.

Every human society creates a certain amount of power which is the direct result of the gross national product. The more technical the society, the higher the amount of power which is created. Its production power includes the production of gods as well as presidents, space ships, types of people, and types of artists: it includes the creation of Great Artists and the absolute Ruler Artists. The places of power in highly technical and governmentally "democratic" societies are filled following a vacancy. No one simply "inherits" them. There are no dynasties into whose laps power falls. The canvas is empty. You must fill it... the place of artistic power is correspondingly empty of personnel. You can fill it... a sentence for those people with great quantities of free-floating production energy may take this form: you must enter into it -- that is, whenever other social production locations are in acute shortage or whenever this position is obviously occupied by an "incompetent," or usurpers.

A public King's Space, a throne-room comparable to the realm of leadership for a president, or a Lord Mayor, is there for the taking in a land like America, in a city like New York. A city like New York will tolerate a vacancy in the position of Great Artist as little as it would an absent Chief of Police or District Attorney. The mediating Orpheus-position is open; it is advertised in the multimedia system, in art studios, patron's palaces, the culture press. Somebody must fill it, the opportunity/undertow is there. The shaman's positions are vacant: the sorcerer's position, the artist-ruler's position. But the one who takes it on is neither elected not installed, he takes it himself -- and faces the consequences (he has to face his people). Warhol grabs his position for medial New York (as Nabokov does in the more limited literary realm). Like all those who grab it, who say at age 15: I will be more famous than Elvis... I will stand on a marble pedestal at 30... Dylan... Freud... They are determinations originating in a certain quantum-feeling of being eligible for this position; and look: one does want someone there... one wants them there... somebody has to be the king... some "subject"... the emptiest highest energy... they like me... It's alright Ma... It's alright Baby... I can make it... I will make it... I will make IT... (to minimize the leadership vacuum).

The astonished realization that, after a certain point, Elvis' or Warhol's followers increased no matter what they did is an expression of "acceptance" once the throne is achieved. Growth is at the power source. The question whether it was "necessary" for Michael Jackson to confirm himself as the "King of Pop" in one of his own videos with the whole world plus Magic Johnson is incorrectly posed. We "need" it, he doesn't. "We" bought Thriller 77 million times (and didn't buy another equally good album 77 million times). But: Some wo/man will be it. And: the media are dynastic. They beget their People (their tribes, their lineage, their serial entourage), from the head on down, from the chief, from the sender, form the magazine, from the place of production. From the place of power. [...]

The tribalism of the various Pop or political affines tends to function democratically because each follower has the same relationship to the head or head-theory: the tribe has one king; the tribal delegation around this position can consider themselves as equals... same rights, same clothes, same thoughts, same music... outside of that, one can be unique... a tribal individual... a tribal individual with a serial relationship to the head. And the head can bow to the "Fhrer" to the "Commander" ...and so there is no political anti-right-wing guarantee built into Pop and Media tribes. (v. 2y, p. 546 ff)

(I would like to thank Christine Kiessling, Kristin O'Rourke, and Mark Saatjian for their help with corrections and editing in the translation of sections of Book of Kings.)